The Lagoon, The Tax, and The 2026 Verdict

Here is the complete email with the new section added at the end, blending your personal stance into the "Queen Media" voice.

Subject: The Lagoon, The Tax, and The 2026 Verdict

Welcome to 2026, Space Coast. As we shake off the holiday fog and look at the year ahead, one issue looms larger over Brevard County than any rocket on a launchpad. It’s darker than a stout at Intracoastal Brewing, and it smells worse than the bait fridge at a marina on a hot July day.

We are talking, of course, about the Indian River Lagoon.

For the past decade, the defining existential crisis of our region has been the slow, agonizing collapse of this estuary. It’s the reason our property values on the water are precarious, it’s the reason manatees have starved by the hundreds, and it’s the reason tourism officials nervously crop photos to make the water look bluer than it is.

Ten years ago, in a moment of desperation, Brevard County voters agreed to tax themselves to fix it. They passed the "Save Our Indian River Lagoon" (SOIRL) half-cent sales tax. It was a massive influx of cash—hundreds of millions of dollars—directed solely at healing the waterway.

But that tax had an expiration date. And folks, that date is staring us in the face.

This year, 2026, is the year the County Commission must convince you to renew that tax. They have to convince you to keep handing over half a cent on every dollar you spend for another decade (or more).

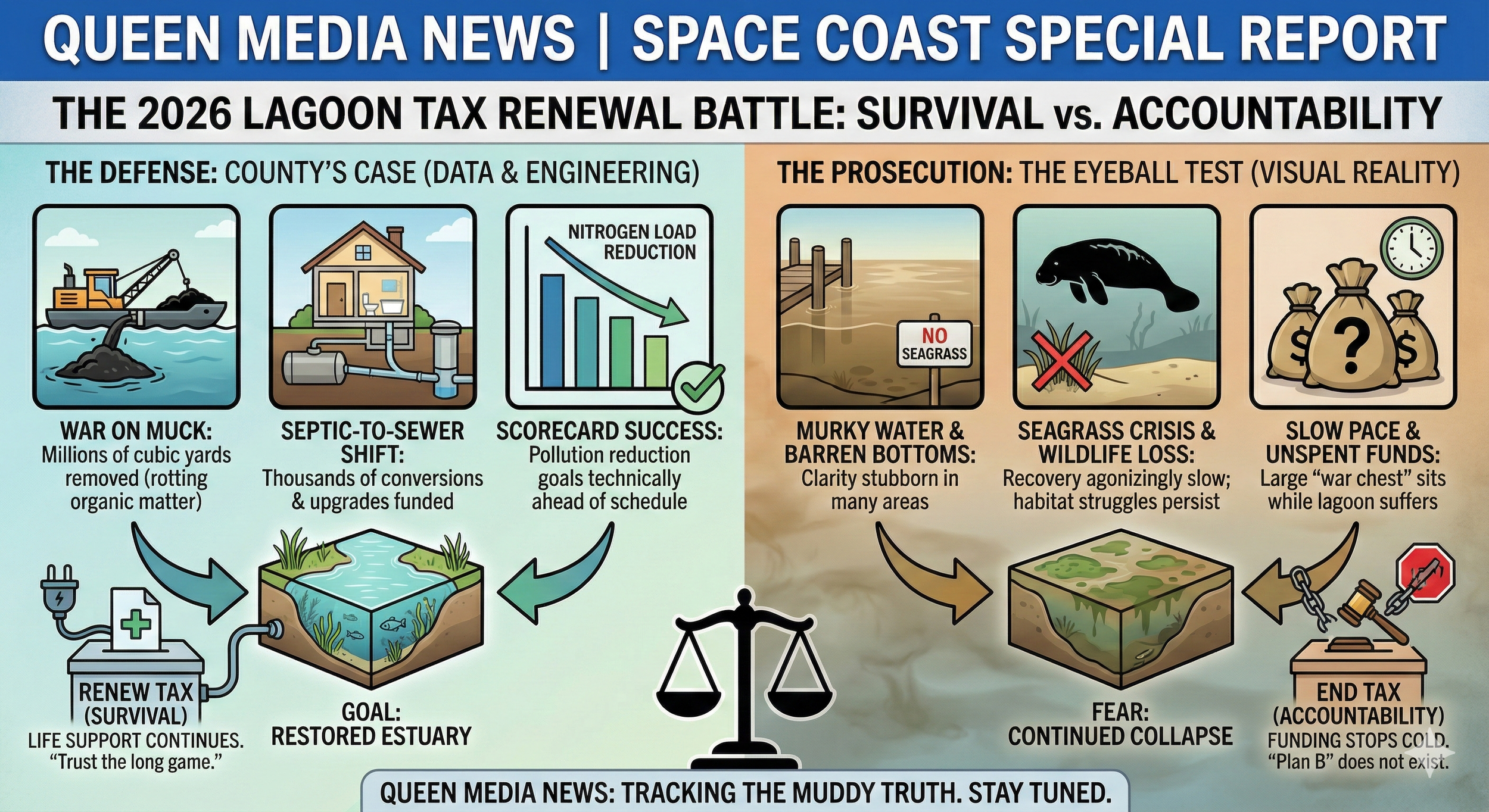

The battle lines are already drawn. On one side, county officials armed with PowerPoint presentations showing tons of removed nitrogen. On the other side, skeptical residents standing on their docks, looking at murky, seagrass-free water, asking, "Where did my money go?"

Queen Media News is diving deep into the data, the drama, and the dollars to set the stage for the biggest local political fight of the year.

The Context: A Decade of Desperation

To understand the 2026 battle, you have to rewind to roughly 2015. The lagoon was in freefall. Massive "superblooms" of algae were shading out seagrass, killing fish, and turning the water a neon, toxic green. The community was furious and frightened.

The diagnosis from scientists was clear: we were treating the lagoon like a toilet. Decades of septic tank leakage, fertilizer runoff from perfectly manicured lawns in Viera and Suntree, and stormwater discharge had overloaded the system with nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus). The lagoon was choking on our own filth.

The solution proposed in 2016 was the SOIRL plan. It was ambitious. It wasn't just about planting mangroves; it was massive infrastructure surgery. The goal was to reduce the incoming pollution load and physically remove the legacy pollution sitting on the bottom.

Voters passed it. The money started flowing—roughly $50 million to $60 million a year, depending on the economy. Tourists paid a chunk of it, which made it an easier sell.

Now, nearly a decade later, we have spent nearly half a billion dollars. The question on the ballot this November, effectively, is: Did it work well enough to keep going?

The Defense: The County’s Case for Progress

If you attend the upcoming workshops—like the one scheduled for this coming Monday, January 5th, in Titusville—you will hear the county’s pitch. And to give credit where it’s due, their data is not insubstantial.

The SOIRL program has become a massive civil engineering apparatus. Here is what the county will tout as they ask for your vote:

1. The War on Muck: This is the unsexy hero of the restoration effort. "Muck" is the black, mayonnaise-like sludge on the bottom of the lagoon—rotting organic matter that releases nitrogen back into the water constantly. The county has spent tens of millions dredging key areas like the Grand Canal in Satellite Beach, Sykes Creek on Merritt Island, and areas near Turkey Creek. They have physically removed millions of cubic yards of this toxic sludge from the ecosystem.

2. The Septic-to-Sewer Shift: This is the hardest, most expensive part. There are tens of thousands of old septic systems on the barrier islands and Merritt Island leaching into the groundwater that feeds the lagoon. The county has facilitated the conversion of thousands of these homes to central sewer lines.

Crucially, just as 2025 closed, the Commission approved increasing grants for homeowners to upgrade existing systems to advanced nutrient-reducing septic systems, offering up to $6,000. They know that to win renewal, they need to make compliance affordable for the average resident.

1. The Scorecard: The county’s primary metric is "pounds of nitrogen removed." According to their latest annual reports leading into 2026, they are technically ahead of schedule on their pollution reduction goals. On paper, tons of poison are no longer entering the water.

Virginia Barker, the director of the county’s Natural Resources Management Department, has been the tireless general of this army. Her message has been consistent: It took 50 years to kill the lagoon; it won't take 10 years to fix it. It’s a generational marathon, not a sprint.

The Prosecution: The Eyeball Test and the Seagrass Crisis

If the county’s argument is data-driven, the opposition’s argument is visceral. It’s the "Eyeball Test."

Walk out to a dock in Cocoa Beach or Palm Bay. Look down. What do you see?

In too many places, the answer in January 2026 is still: cloudy, brown water and a barren sandy bottom.

The critical missing piece—the piece that breaks the hearts of fishermen and environmentalists alike—is seagrass. Seagrass is the foundation of the lagoon. It filters the water, it feeds the manatees, it shelters the baby sportfish.

Despite half a billion dollars in spending, seagrass recovery has been brutally, agonizingly slow. While nutrient loads are down, water clarity hasn't improved enough in many main stems of the lagoon to allow sunlight to reach the bottom and ignite widespread seagrass regrowth. We have seen small pockets of recovery, only to see them wiped out by another summer algal bloom.

The skepticism is palpable. Critics argue that the county spent too much time and money on "demonstration projects" (like fancy stormwater parks that look nice but treat relatively small areas) and not enough on the aggressive, hard infrastructure of sewer conversion.

Furthermore, the manatee die-offs of the early 2020s are still fresh in the public memory. For many voters, if the manatees are still struggling to find food, the plan isn't working fast enough to justify the cost.

The War Chest and the Waiting Game

Another major point of contention in this renewal battle will be the bank account.

The SOIRL program has often collected money faster than it can spend it. There have been times over the last few years where the program had a "war chest" of over $100 million sitting unspent.

The county argues this is necessary fiscally responsible. You can't sign a contract for a $30 million dredging project unless you have the cash on hand. Furthermore, they blame the agonizingly slow state and federal permitting process (looking at you, Army Corps of Engineers and Florida DEP) for delays in breaking ground.

Critics, however, see government inefficiency. They see their tax dollars sitting in an account while the lagoon continues to suffer. "Why are we taxing ourselves more if you haven't even spent what we already gave you?" is a question that will be asked at every town hall in 2026.

The Citizen Oversight Committee—a group of volunteers meant to watch the spending—has generally given the county high marks for transparency, ensuring the money isn't raided for non-lagoon projects (a classic Florida political trick). But even they have expressed frustration at the pace of actual construction.

The 2026 Verdict: Survival vs. Accountability

So, here we are. The stage is set for a bruising political year.

The County Commissioners are in a bind. They know asking for a tax renewal in an economy where housing and insurance costs are skyrocketing is political poison. But they also know that if the tax expires, the restoration stops cold. There is no "Plan B" funding source that can replace $50 million a year. If the tax dies, the lagoon likely dies with it.

Opponents have the easier job: channel anger. They don't need a grand alternative plan; they just need to point at the murky water and say, "You failed."

Queen Media News will be tracking this incessantly. We aren't here to tell you how to vote, but we are here to tell you this: The "trust us, it’s working" phase is over. The county needs to show undeniable results, not just spreadsheets of nitrogen reduction. And the critics need to decide if they are willing to pull the plug on the only life support system the lagoon has, just to make a point about taxes.

It’s going to be a messy fight. It’s going to get muddy. Kind of like the lagoon itself.

For my part, I am in favor of the half-cent raise. We’ve invested too much to turn off the life support now. But that support isn't unconditional. I just need to see improvement—real, visible improvement that passes the eye test, not just the data test.

Stay tuned.